The Immersive Role of Art in Education: Foundations of Learning Through Creative Expression

Apr 7, 2025

7 min read

1

42

0

Abstract

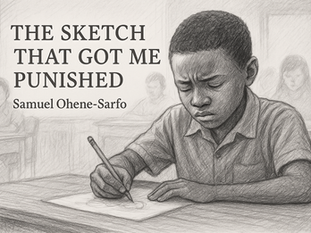

This article explores the essential role of art in early childhood education, emphasizing its profound impact on cognitive, emotional, and physical development. Tracing the historical roots of art as a foundational form of human communication and learning, the piece illustrates how children's artistic expression progresses through defined developmental stages — from early scribbles to more representational forms in the pseudo-naturalistic stage.

Despite this, art is still widely misunderstood and undervalued in many educational settings, often dismissed as a secondary subject or reserved for “the gifted.” This perception overlooks the truth: art is not an extracurricular luxury — it is a core mode of thinking, exploring, and making sense of the world. From problem-solving and spatial reasoning to emotional intelligence and innovation, artistic engagement nurtures skills that are essential across all disciplines. This article calls on parents, guardians, and educators to pay closer attention to the funny little drawings children make — because every scribble, swirl, and mark holds meaning. Art shapes how children think, feel, and grow. Whatever we grow up to become, we all began with a crayon in hand.

By examining the developmental stages of art in children, the article advocates for a more intentional and inclusive approach to art education. It makes a case for positioning the arts at the very foundation of learning — especially during the early years when young minds are most plastic, curious, and open to discovery.

Introduction

Despite the global strides in education and technological advancement, art education continues to be misunderstood and undervalued, even in some of the most developed countries. It is often perceived as a program reserved for those with weaker academic abilities or low IQs. But this notion couldn't be further from the truth. Creativity demands cognitive agility. A creative mind is constantly solving problems, interpreting environments, and interacting with tools and materials to bring ideas to life.

Today, I don't seek to argue, but to share insight into the foundational role art plays in education, especially during the early years. Beyond the beauty of colors and shapes, art is a fundamental language of learning—cognitively, emotionally (affectively), and physically (psychomotor).

Historical Foundations: Art as the Root of Communication and Education

Long before alphabets and written words, humans communicated through art. In prehistoric times, cave paintings were used to document experiences, mark territories, and share knowledge. Ancient Egyptian art introduced hieroglyphs, a visual system of symbols and pictures that laid the groundwork for written language. These gradually evolved into pictographs, and later with contributions from the Greeks and Romans, into alphabets and structured writing systems.

This evolution shows that visual representation came before verbal and written communication, making art not just a creative endeavor but a cornerstone of human expression and education.

Stages of Artistic Development in Children

One of the most significant demonstrations of art’s educational power is seen in the natural progression of children’s drawings. These stages reflect how a child thinks, feels, and physically engages with their world.

1. Scribbling Stage (1–3 years) - Exploratory Expression

Scribbles are records of children’s kinesthetic arm movements over surfaces. Research reveals that scribbling is a medium through which children express emotions and experiences with the external world through a process developing from random scribbles (age 1.5) to named scribbles (age 2). Scribbling is more than learning motor control and coordination, but also a tool of communication that transforms into drawings, words, and stories in later stages.

Characteristics:

Random, uncontrolled lines and marks

Repeated motions—spirals, zigzags, loops, and dots

No recognizable figures or objects

Example: A toddler with a crayon fills a paper with looping circles, dots, and strong strokes—sometimes even going beyond the paper!

Significance:

Development of fine motor skills (grasping, wrist movement)

Early signs of cause and effect ("When I move my hand, I make a mark")

Initiates hand-eye coordination

Stimulates early neural connections related to motion and visual tracking

This stage is not “just scribbling.” It’s the child’s first intentional interaction with a medium, and every stroke is a milestone in brain and muscle development.

2. Pre-Schematic Stage (4–5 years) - Emerging Symbols & Self-Awareness

With improved eye-hand coordination, children turn curved lines into conscious creation of forms, providing a tangible record of their thinking process. They discover that a drawn symbol can stand for something in their picture. Extending lines from circles, they draw typical ‘tadpole figures’ to represent humans or animals. Objects and symbols float randomly on paper and change meaning with children’s observation and experiences. At age 4 or 5, children begin to tell stories and work out problems in their drawings. This is a good time to enter their world through ‘listening’ to their pictures.

Characteristics:

Basic shapes: circles, squares, lines form the building blocks

First attempts to draw human figures: "Tadpole people" (a circle with lines for limbs)

Size and placement are random; little concern for proportion or realism

Use of bold colors without logic—often emotionally driven

Example: A child draws themselves as a round face with long lines for legs and arms coming out of the head. They may also draw a sun in the corner or a floating house.

Significance:

Introduces symbolic thinking—realizing "this shape means something"

Enhances emotional expression ("I used red because I’m happy")

Reinforces self-identity as they begin drawing themselves and family

This is when self-awareness and relationships start showing up in art. They may proudly say, “That’s me and Mommy,” even if the drawing is abstract to an adult.

3. Schematic Stage (6–9 years) - Logical Structure & Repetition

Children use symbols (known as schemas), to represent their active knowledge of a subject. They use a set of symbols, usually with geometric shapes, to identify familiar physical objects or scenes, typically a landscape. A sense of spatial relationship and hierarchy of importance gradually emerges. Objects are placed on a baseline in order of sizes to symbolize the degree of importance the child places on them. Colours are used relating to the real objects.

Characteristics:

Figures have clear parts: heads, torsos, arms, legs, and facial features

Use of a baseline and skyline: green “grass” below, blue “sky” on top

Repetitive symbols used to represent the same objects (a sun always in the corner, trees as lollipops)

Transparent drawings: houses shown with interiors and people inside

Gender distinctions in figures:

Girls often wear triangular or block skirts

Boys may have short lines for legs or trousers

Limbs drawn as straight lines or wing-like extensions

Example: A family in front of a house with square windows, smoke from a chimney, and flowers in a line. The house may be “see-through,” showing beds or people inside.

Significance:

Strengthens visual memory and pattern recognition

Supports emotional and social understanding—drawings often reflect real life (family, home, friends)

Teaches organization and sequencing, crucial for reading and math

This stage marks a turning point where children’s artwork becomes recognizable and story-driven.

4. Dawning Realism / Gang Stage (9–12 years) Real-World Awareness & Comparison

In the Gang Stage, children between the ages of 7 and 9 begin to prioritize group belonging and social identity, which influences how they approach art. They become increasingly critical of their own work, comparing it with peers and striving for greater realism and technical skill. Drawings reflect a growing awareness of proportion, anatomy, and spatial relationships, though perspective and foreshortening still pose challenges. Children may shift from imaginative expression to more rule-based or observational drawing, sometimes suppressing creativity in favor of accuracy. The desire for peer approval can either motivate improvement or lead to self-doubt, especially if their work doesn't align with perceived standards. Despite these struggles, this stage often lays the foundation for more intentional, symbolic, and expressive art in adolescence.

Characteristics:

Growing attention to details—fingers, clothes, objects

Desire for realism, though not always accurate

More interaction between figures—people holding hands, playing

Perspective attempts begin—overlapping objects, ground lines

Increasing self-consciousness: kids start comparing their art to others

Example: A group of children playing soccer, with goalposts and uniforms. The ball is mid-air, and the players have expressions and actions.

Significance:

Encourages critical thinking and self-reflection

Fosters group identity and peer relationships

Children begin to evaluate and revise their work

Art becomes a language for social and emotional storytelling

This is when children may start saying, “I’m not good at drawing,” because they now see flaws in their work. It’s a crucial time for encouragement and emotional support.

5. Pseudo-Naturalistic Stage (12+ years) - Emotional Depth & Realistic Representation

In the Pseudo-Naturalistic Stage, typically beginning around age 12, adolescents approach art with heightened self-awareness and emotional depth. Drawings become more refined, with attention to realism, proportion, and the effects of light and shadow. Perspective and foreshortening are explored with greater seriousness, and figures often reflect anatomical accuracy. Art becomes a tool for personal expression, often revealing the inner emotions, identity struggles, or social concerns of the individual. While some teens strive for photographic realism, others use stylized approaches to communicate abstract or symbolic ideas. Self-criticism can be intense at this stage, as adolescents seek to reconcile their expressive intentions with their technical abilities.

Characteristics:

Focus on realism, depth, and proportion

Interest in shading, facial expressions, clothing details

Subjects may include emotions, scenes, or social issues

Children may mimic comics, anime, or try drawing from life

Example: A drawing of a best friend with styled hair, correct finger placement, and a pet. Backgrounds may include rooms or landscapes with accurate perspective.

Significance:

Enhances observational skills

Develops empathy and emotional expression through themes

Prepares students for conceptual art, design, and innovation

At this point, children see their art as a reflection of their inner world. It becomes an outlet for their thoughts, struggles, and dreams.

How These Stages Support Innovation & Learning

Every stage builds the cognitive scaffolding for future learning:

Scribbling teaches control and coordination.

Pre-schematic drawing builds emotional language.

Schematic work lays the foundation for structured thinking and symbolic logic.

Dawning realism enhances social-emotional understanding and story-building.

Pseudo-naturalism invites critical analysis, observation, and design—skills that feed into STEM, architecture, writing, and entrepreneurship.

Art as the Basis of Innovation

Innovation begins with imagination—the ability to visualize, experiment, and create something new. These are skills deeply rooted in artistic practice. Whether it’s designing a solution, drafting an invention, or developing a product, the mental processes mirror those cultivated in art:

Visualization

Abstract thinking

Experimentation

Emotional connection to ideas

Interaction with materials and media

These traits are not dull. They are the hallmarks of intelligence, creativity, and progress.

Conclusion: Art is the Foundation, Not an Add-On

Art is not just for “the gifted” or the “less academically inclined.” It is for every learner, especially in their early years when the brain is most plastic and impressionable. Those stick-figure families and wobbly crayon drawings are not just cute—they are evidence of developmental milestones.

To truly honor education, we must value the disciplines that nurture the whole child—mind, body, and soul. And that journey starts with art.

Let’s keep the conversation going!Have you seen these stages of art development in the kids around you — at home, school, or through your own journey? I’d love to hear your stories or thoughts in the comments.

If you’re curious to read more about art, education, or creative learning, feel free to explore some of my work:

Thanks for being here — and for supporting creative education in all its beautiful forms.

Reference

Book:

Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1987). Creative and mental growth (8th ed.). Macmillan Publishing Company.

Longobardi, C., Quaglia, R., & Lotti, N. (2015). “Reconsidering the scribbling stage of drawing: a new perspective on toddlers’ representational processes”. Retrieved February 27, 2018, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4543818/

Journal Article:

Matthews, J. (2003). Drawing and painting in early childhood: The role of artistic sensibility. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 22(3), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5949.00359

Website:

National Art Education Association. (n.d.). Why art education is important. https://www.arteducators.org/advocacy-policy/why-art-education-is-important

CreativeKids. (n.d.). Stages of children’s art development. CreativeKids.

https://creativekids.com.hk/stages-of-children-art-development/