Silenced by Peers: The Adolescent Art Crisis in the Classroom

Aug 17, 2025

6 min read

0

28

0

This article, Silenced by Peers: The Adolescent Art Crisis in the Classroom, was originally published by Art Journal Foundation, where it was selected as one of the winning entries in the Spark Creativity 2025 competition https://artjournalfoundation.in/spark-creativity-result-2025

Introduction

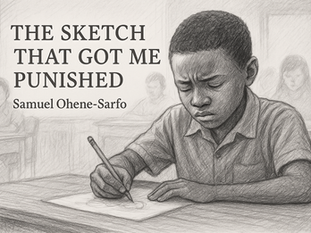

In the course of collecting data for my research project, Drawing the Foundations of Learning – A Developmental Study on the Role of Early Artistic Expression in Ghanaian Classrooms, I visited St. Mary’s School to observe how students at various developmental drawing stages engage with art. During one of the sessions, I posed a simple question: “Who loves drawing or art?” To my surprise, several students responded that they didn’t. As I probed further, I discovered a troubling pattern — many of these adolescents had repeatedly experienced peer rejection, with their work dismissed or unacknowledged by classmates. This recurring lack of validation had quietly silenced their artistic confidence.

Later, while organizing IMPACTion — a creative exhibition project with my Grade 10 students at Ghana Senior High School — I witnessed something radically different. Freed from rigid conventions and working with non-traditional materials, these young artists poured deep, thoughtful meaning into their works. Their shift in thinking and expression reminded me that art should never be reduced to competition. Rather, it should serve as a nurturing ground for cognitive growth, emotional expression, and creative identity.

Drawing from developmental theories — from the pre-schematic stage through to the pseudo- naturalistic stage — it becomes clear that as children and adolescents engage with drawing, pattern-making, and imaginative exploration, they are also developing vital skills in observation, critical thinking, problem-solving, and emotional intelligence. These foundational abilities stretch far beyond the art room, feeding into all other areas of learning.

In this article, I explore how peer influence, rigid evaluation, and lack of encouragement can suppress adolescent artistic voices — and how educators can create safe, expressive environments that empower learners to reclaim their creative selves.

Understanding the Adolescent Shift in Artmaking

Adolescence is a sensitive and transformative period. It is a time when learners begin to form stronger social identities, and their sense of self becomes deeply entangled with how others see them. In the art classroom, this means that the joy of expression can quickly be replaced with the fear of judgment.

In educational psychology, this is often described by Viktor Lowenfeld as the “Gang Stage,” where learners begin to compare themselves with their peers and seek group approval. This is closely followed by what he termed the “Pseudo-Naturalistic Stage,” where young artists become more self-conscious and begin to judge their work harshly against realistic standards. At this stage, if students are not affirmed—or worse, if they are laughed at or ignored—the result can be withdrawal. Not just from art, but from the inner confidence that art helps nurture.

This became clear during my visit to St. Mary’s School, where students in the lower grades showed great enthusiasm and love for art and drawing, while many in the upper grades hesitated to even pick up a pencil. When asked why, some said, “I’m not good at it,” or “My classmates never say my drawing is nice.” Their disengagement was not due to a lack of ability, but from a growing fear of being seen as not good enough.

Art, which should be a safe space for exploration, had become another subject where they felt exposed and judged. This kind of quiet retreat is hard to notice on the surface, but over time, it can quietly erode a learner’s creativity and confidence.

Reclaiming the Adolescent Art Voice: Strategies for the Classroom

If adolescence silences the artistic voice through fear of judgment, then the role of the educator must be to gently invite that voice back. This doesn’t require grand changes, but rather small, consistent shifts in how we frame art, respond to students, and structure creative spaces.

1. Shift the Focus from Skill to Story

Too often, learners associate “good art” with realistic drawing or neatness. But adolescents carry stories—social, emotional, and even political ones—that deserve expression. Begin with prompts like, “Draw how your week felt” or “Create an image of a challenge you overcame.” When the focus moves from technical skill to personal story, students are more likely to share honestly without fear of comparison.

2. Use Anonymous Art Critiques

To reduce peer pressure, occasionally let students submit artworks anonymously for discussion. This allows for open feedback without the weight of identity. Celebrate diverse approaches rather than ranking best or worst. Ask questions like, “What message do you think this artist is sharing?” or “What part of this work speaks to you?”

3. Introduce Non-Traditional Materials

Providing students with non-conventional tools—like cardboard, fabric, leaves, or recycled items—disrupts the idea that art must look a certain way. It encourages play, experimentation, and critical thinking. It also levels the playing field, allowing all students to explore without the pressure of being ‘perfect’ with pencil or paint.

4. Create Peer-Affirmation Spaces

Instead of focusing only on teacher evaluation, build moments where peers offer positive, thoughtful reflections to one another. A “one thing I love about your work” wall or a short gallery walk with written feedback slips can help students see themselves through kind, appreciative eyes.

5. Avoid Comparison-Based Praise

While it’s natural to celebrate excellence, be mindful not to elevate one student’s work as the standard. This can unintentionally discourage others. Instead, highlight effort, creativity, process, or emotional honesty. Every student should feel that their voice is valid and worth listening to.

These small shifts build a culture of safety, trust, and growth—where adolescents learn that art is not about being the best, but about being real.

IMPACTion: A Living Example of Creative Empowerment

I witnessed the true potential of these strategies come alive during our recent student exhibition titled IMPACTion – A Creative Response to Societal Problems. The theme challenged students to produce artworks that addressed real issues using the framework of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Each learner chose a goal that personally resonated with them—ranging from quality education and climate action to gender equality and mental health—and created a visual piece that spoke to it.

What was remarkable wasn’t just the final works, but the transformation I observed in the process. Freed from the pressure to conform to traditional materials or techniques, students worked with recycled fabric, clay, collage, wood scraps, and even natural pigments. As they shaped their concepts, their thoughts became more intentional. Their conversations became more thoughtful, and it was clear they were discovering what really mattered to them through the art they created.

Some students who were previously quiet in class took bold creative stances. One student used burnt paper and charcoal to illustrate how bushfires disrupt schooling in rural communities. Another combined twigs, sand, and plastics to explore how human actions can both help and harm efforts to protect life on land. These were not just artworks—they were acts of thinking, feeling, and advocacy.

Perhaps most importantly, IMPACTion showed that when art becomes a voice—not a performance—it unlocks genuine growth and self-discovery. The learners were not trying to prove their artistic skill; they were trying to be understood. And because of that, their work became deeply human, thoughtful, and impossible to ignore.

Conclusion: Art as a Voice, not a Contest

Adolescents are not just growing students — they are becoming thinkers, feelers, and citizens. In this becoming, art can either be a safe companion or a silent critic. If we are not careful, the way we teach and talk about art can unintentionally close the door on creative expression, replacing it with fear, competition, or self-doubt.

But as I have seen in my own classrooms and during the IMPACTion exhibition, when we shift the focus from technical perfection to personal connection, young people find their voice again. When we create space for experimentation, when we listen rather than label, when we affirm effort and intention over polish and praise — we empower our students to express their full selves.

Art in adolescence should not be about who draws best, but about who dares to speak. As educators, our greatest task is to protect and nurture this voice, especially when it begins to waver. Because in doing so, we don't just teach art — we teach courage, identity, and the freedom to think and express differently.

Bibliography

Eisner, E. W. (2002). The Arts and the Creation of Mind. Yale University Press.

Gardner, H. (2011). Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books.

Lowenfeld, V., & Brittain, W. L. (1987). Creative and Mental Growth. Macmillan.

Winner, E., & Hetland, L. (2000). The Arts and Academic Achievement: What the Evidence Shows. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 34(3–4), 3–10.

Ohene-Sarfo, S. (2025). The Immersive Role of Art in Education: Foundations of Learning Through Creative Expression. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15164583

Opoku-Asare, N. A. (2015). Art Teachers’ Beliefs and Pedagogical Practices in Ghanaian Basic Schools. Journal of Education and Practice, 6(19), 40–50.

UNESCO-IBE (2010). Arts Education in Africa: Emerging Perspectives from Ghana, Nigeria and South Africa. Geneva: International Bureau of Education.